I have always wanted to attend the Olympics, indeed, as a huge sport lover (yes watching sport on television is a sport to me) being able to attend such a competition would be phenomenal. Then, two weeks before I left for Edinburgh, I discovered a documentary about the Highland Games. For twenty minutes or so, I was stunned on my sofa by what I was seeing on television – no, but who has the idea of taking a tree trunk and turning it into an event? I absolutely had to go and see it for real, but it quickly went off into a corner of my head with the last final touches before I left for my university exchange.

However, what was my surprise, when I saw the list of events for the university’s fresher’s week, to see a one-day expedition to the Pitlochry Highland Games. I could not resist the temptation.

BUT BY THE WAY, WHAT ARE THESE HIGHLAND GAMES?

These are ancestral games, originating in the Scottish Highlands, which nowadays take place all over the country during the period from May to September. Each region organises its own games, but the atmosphere and events remain the same in order to pass on and celebrate Scottish culture. Halfway between sport and culture, halfway between athletics and strongmen’s competitions, thanks to this article, you will want to take part in this beautiful event.

I will try to give you a thorough review of the Highland Games I attended. The Highland Games are world-renowned events, held not only in Scotland, but also around the world, where Scottish diasporas exist, although the focus of this article is on Scotland, and Pitlochry in particular. Highland Games events are complex to categorise and conceptualise given their multi-layered nature and scope, involving a multitude of activities each based on diverse local histories and traditions.

These Games have gained great notoriety in countries such as New Zealand, Canada and the United States, becoming a cultural spectacle in local communities. One of the main factors behind the creation and continuity of these events, which has helped to maintain their presence overseas, has been the global diaspora of Scottish migrants who wanted to keep the traditions, clothing, culture and music of the Highlands alive. This cultural contribution by Scots, forced to emigrate in the 18th and 19th centuries due to Highland Clearances and other push factors such as poverty, is still very important today, both in Scotland and around the world.

Furthermore, as an event, each Highland Game is unique in its setting, format, history and competition! This is why the notion of Highland Games as a combination of a community event and an attraction is an easier approach to understanding their raison d’être and their current role in Scottish society.

Moreover, through its history, one can learn more about Scottish culture, as these games are deeply rooted in the past and are surrounded by folklore and legends.

A BIT OF HISTORY FIRST

A historical review is essential to understand how an event is strongly rooted in a community that has preserved its cultural and social significance over a long period of time, despite commercial pressures.

It is difficult to determine precisely when and where the Highland Games took place, as there are virtually no records, as most of the information about Highland customs and traditions has been passed on by word of mouth to subsequent generations. One explanation for the Gaelic origin of the Games is that they were organised in Argyll, in the west of Scotland, by a community known as the “Scotti” who emigrated from Northern Ireland between the 4th and 6th centuries AD, bringing with them an early form of athletics known as the “Tailteann Games” which continued in Scotland until about 1180 AD.

A popular explanation among historians is that the origin of the Games would go back to the 11th century and would be attributed to King Malcolm III of Scotland who organised a running competition in order to recruit the best runner to be his messenger. Then, step by step, the different clans of Scotland decided to get together in order to make agreements and then to finish with sports jousts.

In rural areas, these events were used to demonstrate feats of strength with competitions between farmers or local teams, friendly rivalries that increased and strengthened social cohesion within the different communities and provided fun for locals, visitors and competitors.

It was not until the 19th century that the games in their present form were developed, since a law in 1746, following a battle, forbade gatherings, bagpipes and kilts, for fear of seeing the Highlanders revolt again.

According to the programme received in Pitlochry, here is a more detailed history of the Games in this community:

« However, the origins of the Highland Games are lost in the mists of time and may date back to the 4th or 5th century. At that time a Celtic people called Scotti crossed the Irish Sea from County Antrim and settled in Dalriada, now Argyll. They began to play games of running, horse-racing and wrestling. As the Scotti spread throughout the Highlands, gradually becoming known as Scotsmen, their gaming traditions spread.

But the clan system that developed in the Highlands also became fertile ground for the feats of strength of the young warriors. Over time, other events such as flute, violin and dance were added. The events were performed in no particular order.

Unfortunately, all these manifestations of Highland culture were promptly repressed by the London government following the Battle of Culloden in April 1746, after the defeat of the Jacobite rebels supporting Prince Charles Edward Stuart. Although the Act of Proscription was repealed some 40 years later, Gaelic culture was well and truly set aside. Fortunately, the old traditions began to return to Scottish life at the beginning of the 19th century, encouraged to a large extent by the enthusiasm of the famous novelist Sir Walter Scott. The “modern” games as they are known today in Pitlochry were among the first in 1852, four years after Queen Victoria’s approval of the Braemar Games in 1848.

In 1852, when the people of Pitlochry (about 300 inhabitants at the time) decided to launch their own Highland Games, they could not have imagined that the town, which now has almost 3,000 inhabitants, would still be hosting the event 167 years later. This is, of course, the 167th anniversary of the founding of the Games; in fact, there were only 150, following the interruption of the games during the two world wars. »

And the 2019 edition was, according to the locals with whom I spoke, very similar to the first edition and very close to the ethics of the founding fathers.

Nowadays, the biggest Scottish sports competition is the Dunoon Cowal Games, where more than 3,500 people take part. This makes it an extraordinary event, however, I am glad to have attended the Pitlochry event, less famous but perhaps more authentic.

A DAY IN PITLOCHRY

The Scottish flag is flying almost everywhere around us in the town and around the land, and I can feel the inhabitants deeply engaged with the desire to be independent. Indeed, in this Perthshire town, a few stalls in the main street call for a new referendum, especially with the advent of the Brexit. I keep my ears open as I don’t have time to stop (I don’t want to miss the trunk toss) and I hear the supporters of independence encouraging tourists and locals alike to learn about Scotland and its future as a possible independent state. Although I’m keen to learn more from locals about the Brexit issues and a possible new referendum for independence, I’m thinking about why I’m also walking down this street… The trunk throwing is calling me… as I don’t know what the programme is, I want to have a front-row seat for the festivities to begin.

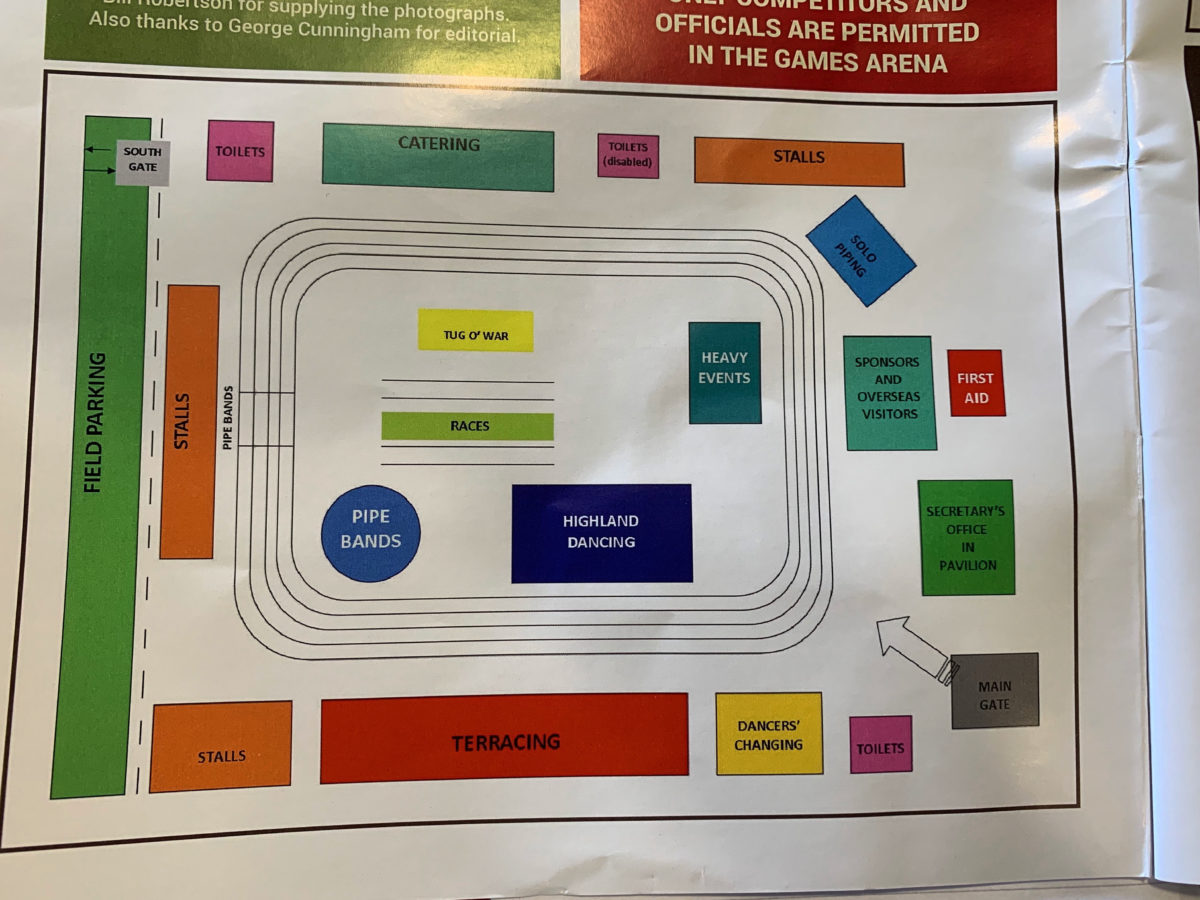

After a 5 minute walk, we arrive at the field where the festivities take place. It is simply a huge field with bleachers on the left side and on the other side, stands of local food, but also stands of “souvenirs”. We buy the programme for the day so we know where to go. The weather remains slightly grey (typical of the country you might say), but the sun will make a few appearances during the day, but so will the rain. So yes, real British weather is present to welcome us.

We let ourselves be carried away by the voice of the speaker who announces the results as well as the future competitions. I feel great pride around me, from families who have come to cheer on their clan to simple tourists like me who have come to discover a little more of this Scottish culture, which is certainly completely unusual but surprising and which will win the favour of my heart at the end of the day. I notice how popular this event is in the local life and we finally let ourselves be seduced by the beautiful melody of the bagpipes, which, although it can be annoying in the long-term, remains in my eyes the main emblem of this Scottish culture that I am keen to discover at the beginning of Erasmus.

The festivities begin! Kilts are out, compulsory for participants (except for those running or biking). Here is a little tour of the activities I was lucky enough to see during this day.

TRADITIONAL DANCES – HIGHLANDS DANCING

We attended all the dances scheduled during the day, although sometimes we weren’t in the bleachers since all the events were almost at the same time, we preferred to stay towards the so-called “strong” events.

There are five types of dances, all of which are the result of legend and are widely recognised as being among the most complex and sophisticated folk dances in the world.

THE HIGHLAND FLING

This is the most famous and oldest of the traditional Scottish dances.

According to tradition, the ancient kings and chiefs of Scotland used Highland dances to select the best men for their retinue. These dances tested the strength, endurance, precision and agility of a warrior.

The ancient warriors and clansmen performed this dance on the small round shield (called a targe), which they carried into battle. Most Targes had a pointed steel spike about 5 to 6 inches long that protruded from the centre, so dancers learned to move with great skill and dexterity early on, as wrong or careless step could be more than a little painful.

It is said that the dance was inspired by the antics of a deer on a Scottish hillside and the dancers raising their arms mimic the antlers of the animal. Danced with vigour and exuberance, it is now highly stylised and requires the utmost technical skill and accurate timing.

.

It has become the solo classical dance in modern dance competitions and is often selected in competitions to decide who will be judged as the best Highland dancer of the day.

The word “fling” has entered the English language to mean a particularly carefree and happy time, which is not very representative of the image of the “dour Scot”, a severe, tough, stubborn or unshakeable Scot.

SEANN TRUIBHAS

It is pronounced “shawn trews” and the literal translation of Gaelic means “old trousers”. This dance is reputed to date from the 1745 rebellion that the Highlanders lost and therefore were no longer allowed to wear the kilt.

Seann Triubhas is a celebratory dance developed in response to the repeal of the Proscription Act by the English in 1747, which restored to the Scots the right to wear their kilts and play the bagpipes.

The first part of the dance, consisting of graceful, flowing movements, is meant to mock the restrictions imposed by foreign trousers, while the movement of the second part clearly depicts the legs shaking defiantly and getting rid of the hated trousers and returning to the freedom of the kilt. The dance then progresses from slow to fast time as a final celebration of the rediscovered freedom.

HULLACHAN

The Hullachan, to give it its Gaelic name, is a four-person dance also known as “the Reel o’ Tulloch”, as it is said to originate from the small village of Tulloch in Perthshire. The minister was late and the congregation, to keep warm, began to dance the Reel Steps and swing into each other’s arms in an alleyway. Although the dancers dance in fours, they are not judged as a team, but individually.

It was this dance that I had the pleasure of seeing from the front. To the sound of the bagpipes, the 4 dancers were impressive, especially for their young ages.

SAILOR’S HORNPIPE

Although it is not a Scottish dance, it has been part of the Games tradition for a long time. The costume worn is based on the uniform of a British sailor. The name originally comes from a popular English wind instrument that was made of wood or ox horn and was common in Britain in the 1700s. Small, cheap to make and requiring no great skill to master, it was the people’s favourite instrument and then, with the limited space onboard ships, it became popular with sailors.

Later, the name hornpipe became attached to a number of melodies of a particular rhythmic style, played on the bagpipes, and later still, the dances accompanying this style are also known as “Hornpipes”.

If one looks at the dancer’s steps, it is clear that the moves are related to naval activities, such as climbing ropes, lifting anchor, seeking land, greeting the captain, etc.

IRISH JIG

Another popular import is Jig, which is danced in a traditional red and green dress. This dance is a humorous caricature and a tribute to the Irish step dance. If it is danced by a woman or a girl, it is either a woman in distress blaming her husband, a woman tormented by elves, or a washerwoman chasing boys (or children in general) who have soiled her laundry with the fact that the woman’s fist is the symbol that she wants to beat the children, the elves or the husband. If it is danced by a man or a boy, it is the story of Paddy’s Leather Panties, in which a careless laundress has shrunk Paddy’s leather panties and he waves his razor at her angrily. So many legends!

Heavy Contests

This is truly the soul of these Games. For some, the heavyweight events can be seen as the embodiment of the Highland Games, although other events have always been an integral part of the Games, such as hill running, dance, wrestling, bagpipe music and sometimes recitals of Gaelic poetry.

The weight events were the ones I was particularly looking forward to for his trunk throw. For the record, Baron Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympic Games, introduced hammer throwing, weight throwing and tug-of-war after attending a demonstration of the Highland Games at the 1889 Universal Exhibition in Paris. Leaving aside tug-of-war, which is no longer a part of the Olympic Games, the other two disciplines are still part of the events today.

We gather around the field in order to get a glimpse of the competitors for these events. First, there is the competition for the locals which consists of 7 men and 1 woman and then, later in the afternoon, there will be the competition open to everyone with men from all over the world.

Obviously, I immediately find a favourite to cheer for. It is true that he immediately stands out from the candidates by being the only one in his twenties who is visually appealing. His name? David JNR (for junior)! Yes, junior because Daddy also competes under the name of David SNR (for senior)… Nice family.

So, for a few hours, we will see these brave people compete and represent their region, even if they are almost all from Pitlochry or Perthshire. The competition is simple, each person competes by event and the best one gets a prize. There is no overall ranking, but in the end, despite everything, the best of all the events will be chosen.

We find a seat, just next to the field to watch the competitions, and this in a slight Scottish rain :

TOSSING THE CABER

It’s the highlight of the Highland Games, or let’s say rather that’s why I’m attending these games. Finally, I’m going to see the famous tossing of the trunk, which is called “tossing the caber” in Scottish dialect.

I will need the explanations of a charming spectator, perhaps from David’s family, who knows, to help me understand in detail the specifics of this event. Because yes, it is not just a simple trunk throw: there are rules.

What is important in this event is not the distance of the throw but rather the way it is done. The competitors try to turn a trunk weighing up to 70 kilos so that it falls back to 180 degrees to the throw. Thus, the distance covered by the trunk is completely secondary. The trunk measures approximately 5.5 metres (18 feet).

The competitor lifts the trunk by placing his or her hands crossed under the narrowest end, pressing the length of the trunk against his or her shoulder, then runs as fast as he or she is able, stops and throws the end he or she is holding so that it lands on the ground and the other end passes over it. The competition is judged using an imaginary clock face. The competitor throws at 6 o’clock. He/she throws the raiser so that it lands in the centre of the dial. A perfect throw is one that passes straight through, with a slight landing at 12 o’clock precisely.

Finally, I might as well tell you that I had a lot of fun watching these people throw trunks. Atypical for sure but engraved in the minds of the spectators, especially tourists.

THROWING THE WEIGHT OVER THE BAR

Each competitor must throw a weight, which weighs 56 lbs (25.4 kilos), under a bar. As in the High Jump, each athlete is allowed three attempts for each height but must throw it with one hand. From a distance, we feel like we are watching a big potato throw, as we do not have a good view of the event from our seats.

A lot of strength is required, although this is almost contradicted by the very nonchalant attitude of most of the competitors. Even my David, quite frail compared to his fellow competitors, throws this stone with disconcerting ease. It seems that this weight is a feather that almost easily passes a height of 5m when you see these competitors so at ease. It’s impressive!

PUTTING THE STONE

Traditionally, this was the first event in the heavyweight programme. It was originally a smooth stone from the nearest river bed, sometimes shaped by a local mason. The shape and weight of these stones varied greatly, especially those used for strength testing, where stones weighing up to 265 pounds (120 kilos) were used!

Today, the weight of the stone is either 16 pounds (7.25 kilos) or 22 pounds (10 kilos). The participant must throw the stone as far as possible and the technique used is essentially the same as the weight throw, one of the track and field events.

THROWING THE HAMMER

This event represents an old contest where young locals competed to see who could throw the sledgehammer the furthest. Throwing the hammer is also an Olympic event, although the hammer thrown at the Highland Games is quite different from the one you usually find in your tool shed. It consists of a metal ball, which can weigh up to 22 pounds (10 kilos), tied to a wooden handle. Also, unlike the Olympics, athletes are not allowed to spin while throwing the hammer.

Instead, they stand with their backs to the field and swing the hammer over their heads, then rotate it 180 degrees and throw it as far as they can. Athletes also wear special boots, with long blades attached to the base, to ensure that they stay securely attached to that part of the ground. Besides, it was David who won this event.

THROWING THE WEIGHT FOR DISTANCE

It is the most graceful of heavy events, combining rhythm and power. The weight is a 28-pound (12 kg) iron sphere on a chain with a handle at the end. It is thrown from behind a reference point (“trig” in English), with a run of no more than 9 feet (about 3 metres). The thrower swings the weight to the side and then spins it behind him, allowing the weight to drag as far as he can. He then waltzes once, twice, and in the third round, he spins the weight and throws it as far as he can. One of the main challenges of this discipline is that the thrower, having gained a lot of speed while spinning, stops at the reference point while keeping his balance.

TUG O’ WAR

When I thought that the Scots could no longer surprise me, the time had come to untie the rope for the unmissable tug-of-war event. A guaranteed laugh but also a lot of admiration for these four teams, grouped by clan members who still compete fiercely. We really had a front-row seat as our benches were directly opposite this competition.

It was an Olympic event until 1910, but it remained very popular throughout Scotland, pitting teams of up to 15 people against each other in a fiercely contested trial of strength and tactics. To win, a team must pull their opponents forward 6 feet (about 2 metres) using the rope.

PIPE BAND COMPETITION

During the day, bagpipe sounds were heard intermittently, since there is indeed a competition also for the various groups, called “pipe band” in English, of the region.

The musical part of the games consists of a large gathering of bagpipes. The orchestras mainly play together at the beginning and the end of the ceremony, with favourite musical pieces such as Amazing Grace or Scotland the Brave.

OTHER EVENTS

I had also heard of other events such as haggis throwing (a Scottish national dish) or a porridge competition, but we didn’t see that.

Pitlochry also included track and field events such as 100m races, relays and high jump. Cycling events were also organised. These competitions are organised for locals but for some of them visitors can take part, such as the mum and dad races. The different categories in these events include young people, adults and people with disabilities.

REFLECTION ON THESE GAMES – IMPORTANCE OF SUCH EVENTS FOR THE legacy OF A CULTURE

It was an incredible day full of surprises, for me, not knowing much about Scottish culture. The Highland Games are a great example of how tourism can help to discover a community, yet there are some issues to consider.

What history does not tell us is how much the original Games cost. For example, for Pitlochry, which is still run entirely by unpaid volunteers, the costs are around £40,000, 35% of which is spent on prizes and trophies. Setting up the pitch for the one-day event, relocation of the field, traffic control, toilets, tent hire and judges’ fees still account for 33% according to the official event brochure. The Pitlochry Highland Games are self-financing and depend entirely on programme advertising, local merchants and sponsorship. The largest source of income comes from the people attending the Games on that day. If the number of spectators is less than 5,000, the balance starts to fall into the red. It is clear that the Games are very dependent on the weather as well. Fortunately, it was quite good that day.

The challenges that non-profit gaming organisations face in continuing the Scottish tradition are, in my view, particularly relevant when studying the tourism industry. One particular issue is the recognition of the dangers that the more commercial priorities of event management pose to the rich cultural heritage that underpins the Highland Games and which could easily be overlooked by a more professional organisation.

In Pitlochry, the Games are run entirely by the community and not by a company which is naturally more interested in making a profit than in organising a day which is culturally important to the Scots. And this is what makes this event so charming because it feels like a sincere local investment.

The relationship between tourism and sporting events is closely linked and I am very interested in it. It is certainly in this field that I would like to focus my career. The role of these events is often seen as a major catalyst for local and national economic development. As a result, the origins of event management today mark a shift from community initiatives, such as the Highlands Games, to more professional events, managed by event organisers as part of a wider professionalisation of the field. It is simply a matter of taking care to maintain a legacy and the ongoing role of local communities and volunteers who are dedicated to the development of their culture. The enhancement of local heritage and community pride are two important points that need to be reflected in the organisation of such an event (which is the case in Pitlochry, but perhaps not in other Highland Games)!

Thus, these Games are both a local leisure and tourism stake. Moreover, the Highland Games can be classified into four categories according to the academic article by E. Lothian’s academic paper “Tourism games and the commodification of tradition” which I reviewed for a report in my Sports Business Event course in Edinburgh. It shows the evolution of the names. Firstly, the Highlands Games can be called ‘Traditional Games’, then ‘Modern Games’, then ‘Community Tourism Games’ and finally ‘Commercial Tourism Games’. This is why these Games must be protected, which is what the Scottish government has done, seeing that they attract visitors and tourists every year not only from Scotland or the UK but also from abroad (I am the evidence).

Thanks to the management of VisitScotland and the Government, who are happy to let the different regions organise their own Games and help them at the same time, everyone can enjoy the Scottish culture and heritage that is worth discovering and promoting! The fact that the Highland Games continue to exist as a sporting, cultural and community event demonstrates the importance of historical links and traditions in shaping authentic tourism products and unique visitor experiences. A powerful community and tourism event that provides a cohesive focus.

But let’s not forget that it all started with a simple reportage that caught my attention because of the throwing of the trunk! Okay, I’ll leave you with a video:

Thanks to this, I was able to discover a magnificent facet of the country that welcomed me for 4 months. So, if you go to Scotland, try to attend some Highland Games, you won’t be disappointed! I promise.

.