My Egyptian journey continued to Luxor, a city that, for me, is the true heart of Ancient Egypt. In a brief introduction to Luxor, I explained the symbolic duality of the city, between east and west and life and death. To the east, we have light, life, and rituals. But today, we focus on the west bank, the dark side, where mysteries and eternity blend—the famous “side of death.”

The Valley of the Queens: Discovering the Great Ladies of Egypt

Our adventure for the day began at the Valley of the Queens. Honestly, I wasn’t sure what to expect. History books do not often mention this place, and that is a shame because so many great women are buried here. Having reserved the whole day to explore this mysterious “side of death,” we visited three queen’s tombs. Which ones? I have racked my brain, but I can not remember.

Our guide, a certified Egyptology enthusiast (and trust me, it’s crucial to have someone like her guiding you, I talk about it here), took us on a journey through the past, sharing the fascinating lives of these women who were far more powerful than we could have imagined.

Unfortunately, guides were not allowed to accompany us inside the tombs, so we had to rely on our imagination. Picture a peaceful place hidden between the hills of Luxor, bathed in an almost surreal atmosphere. Early in the morning, it is calm… perfect for the eternal rest of these queens and concubines of the pharaohs.

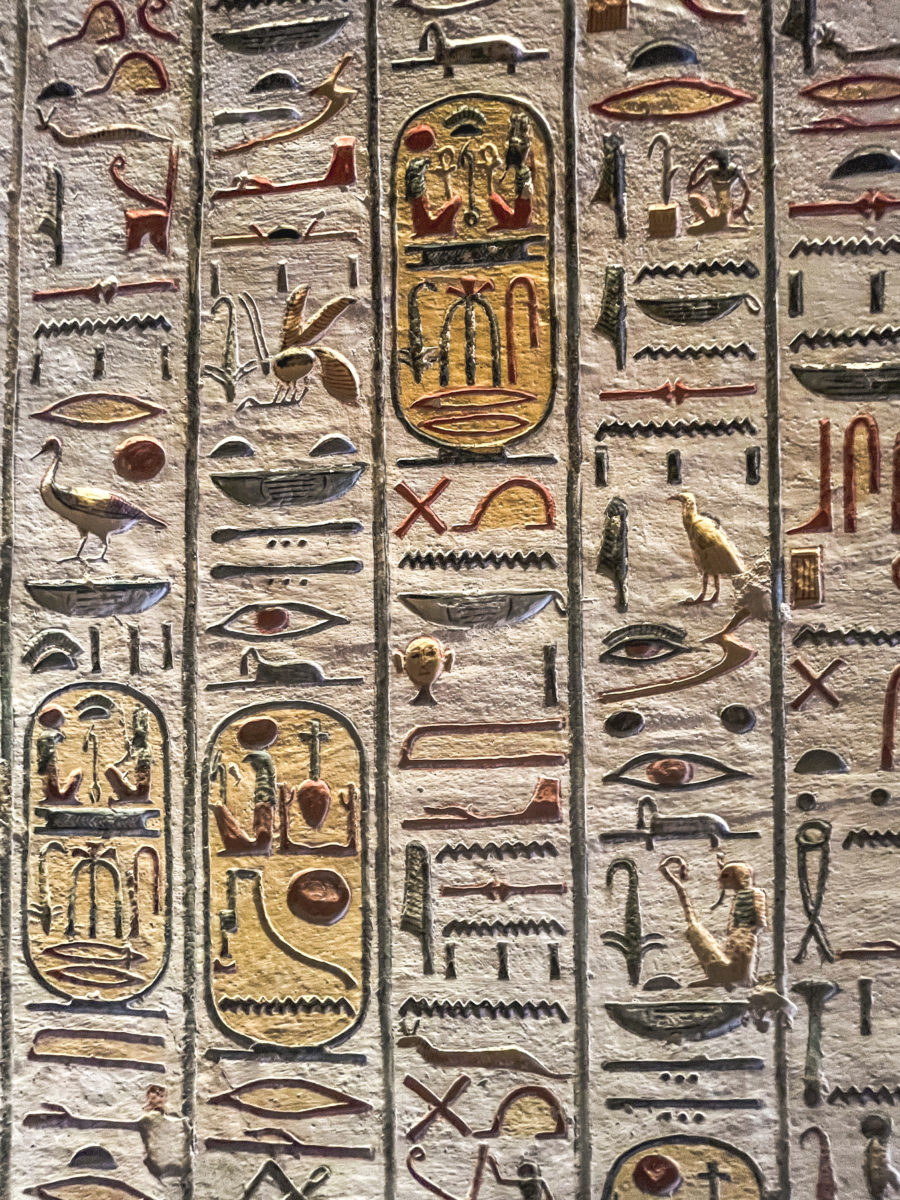

With around 90 tombs, the Valley of the Queens is a real hidden treasure. Some of the tombs are true masterpieces, and discovering these colourful frescoes only increases the excitement for what awaits us next at the Valley of the Kings. The tomb of Nefertari, the great royal wife of Ramses II, is one of the most beautiful, a true legend. Unfortunately, it was under renovation during our visit. So, we decided not to pay extra to see it when it was not at its best… but one day, I will return just for her!

So, we explored three other tombs. The frescoes were incredibly well-preserved, and the colours seemed to have defied the centuries. With each tomb, I felt like I was stepping through a doorway into a mysterious past, where these women played a much more significant role than one might imagine.

And then, I need to confide something to you. Some believe it, others don’t, but I have always been fascinated by Ancient Egypt. After a few kinesiology sessions, I learned that, in a past life, I might have been… a woman of intrigue in ancient Egypt. I do not know all the details, and I am not looking to find out more, but I felt, deep down, as I walked between the pyramids and here in Luxor, a strange sense of familiarity. As if these places were not entirely unfamiliar to me. So, who knows… maybe I know someone buried in this famous Valley?

The Valley of the Kings: Home to the Great Pharaohs

Next, we headed to the legendary Valley of the Kings.

Nestled on the west bank of the Nile, the Valley of the Kings is home to about 65 tombs discovered so far, numbered from KV1 to KV65 (KV stands for King’s Valley). This sacred site was chosen by the pharaohs of the New Kingdom (or Egyptian Empire) to hide their tombs and avoid looting. Unlike the pyramids, these tombs were directly dug into the rock, offering a more discreet sanctuary while being beautifully decorated.

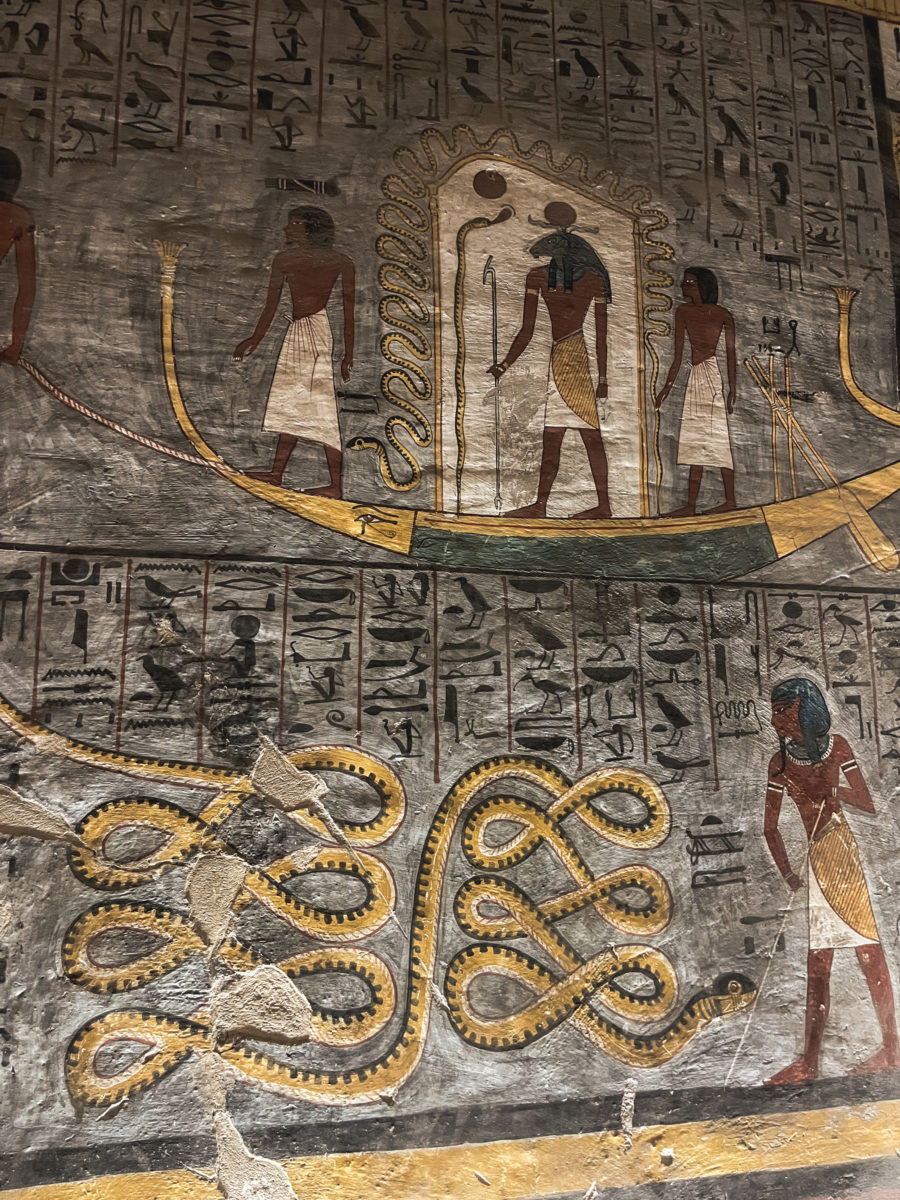

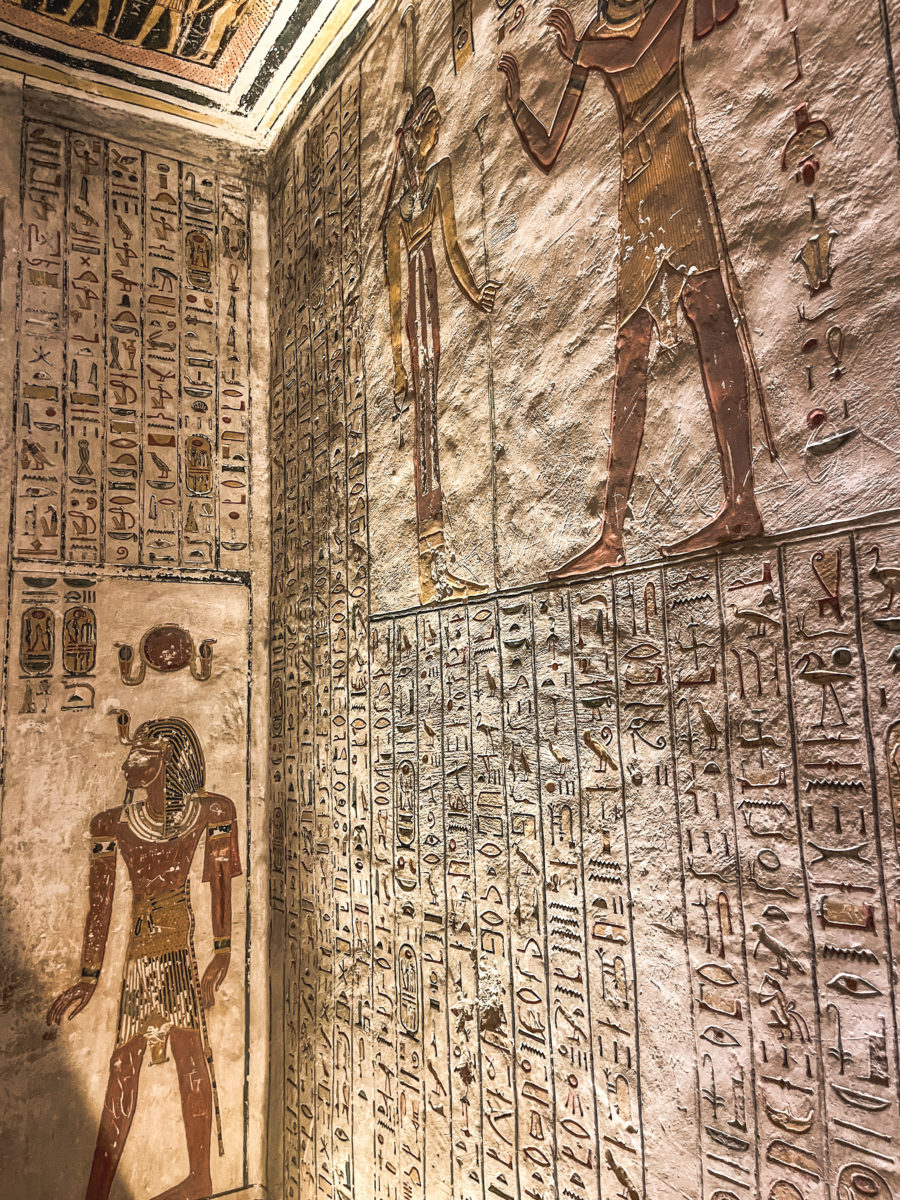

The architecture of these tombs follows a precise pattern: a descending corridor leads to one or more burial chambers, whose walls are adorned with frescoes and hieroglyphs depicting the journey of the deceased to the afterlife. These mythological scenes illustrate the pharaoh’s passage into the world of the gods, his judgment, and his ascension to eternity, under the protection of Osiris and Ra.

For your information, the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt spans from around 1550 to 1070 BC. It is one of the most prosperous and powerful periods in Egyptian history, marked by military conquests, cultural and artistic advancements, and the construction of numerous temples and monuments.

We count the following major dynasties during the New Kingdom era:

- 18th Dynasty (~1550-1295 BC): The peak of Egypt, with pharaohs like Ahmose I (founder), Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, and Tutankhamun.

- 19th Dynasty (~1295-1186 BC): The reign of Ramesses II, one of the greatest Egyptian rulers.

- 20th Dynasty (~1186-1070 BC): A progressive decline with Ramesses III, followed by the fragmentation of the empire.

At the entrance, we headed to the main building, where we purchased our entry tickets (the price often changes, for example, it was not the same as what was listed in our guidebook). This allowed us to visit three tombs open to the public, which change regularly. Authorities apply a rotation system to preserve these millennial treasures from mass tourism.

If we wanted to visit certain legendary tombs, an extra fee was required, notably that of Tutankhamun, which offers little to see, as it is better to admire the artefacts at the Cairo Museum. On the other hand, the tomb of Ramesses VI, with its magnificent frescoes, or that of Seti I, the most spectacular but also the most expensive (around 60 euros), was well worth the detour.

So, we visited three tombs and paid the extra fee for that of Ramesses VI. Our day’s visit was all about Ramesses.

As soon as we passed the Visitor Center, the landscape was breathtaking: a vast desert of ochre stone, surrounded by cliffs. No majestic temples or obelisks here, just discreet openings carved into the mountain. It was hard to imagine that beneath my feet lay the tombs of Egypt’s greatest kings!

To avoid a long walk under the sun, we took the little train (a few extra Egyptian pounds) that connected the ticket office to the tombs, where our guide began her first explanations. Indeed, just like at the Valley of the Queens, our guide could not accompany us inside the tombs. So, the explanations took place outside before we immersed ourselves in these burial chambers adorned with sculptures and vibrant paintings.

The KV2 tomb, dedicated to Ramesses IV, was the first one we visited. It’s also one of the largest and most accessible in the Valley of the Kings. Built quickly due to the short reign of the pharaoh (1155-1149 BC), this tomb impresses with its long corridor decorated with hieroglyphs and stunning frescoes, illustrating the king’s journey to the afterlife.

Among the remarkable works, there are excerpts from the Book of the Dead and a beautiful representation of the goddess Nut on the ceiling, symbolizing the rebirth of the sun. The burial chamber, at the end of the gallery, once housed a massive red granite sarcophagus, now empty.

The KV2 tomb was visited as early as antiquity, as evidenced by inscriptions left by Greco-Roman travellers. Thanks to its excellent preservation, it remains one of the most spectacular tombs to explore in the Valley of the Kings. Easy to access and richly decorated, it offers a fascinating glimpse into the beliefs and funerary rituals of the Ramesside period.

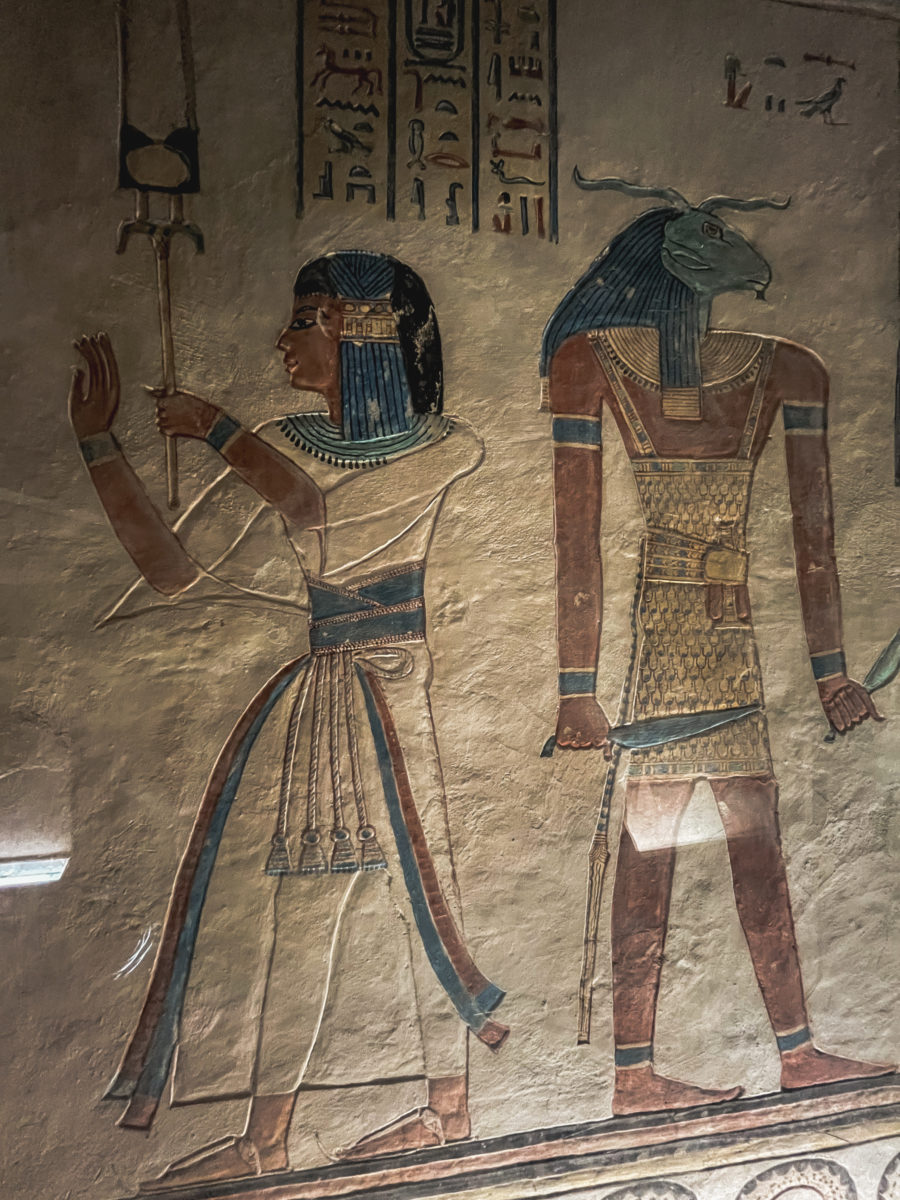

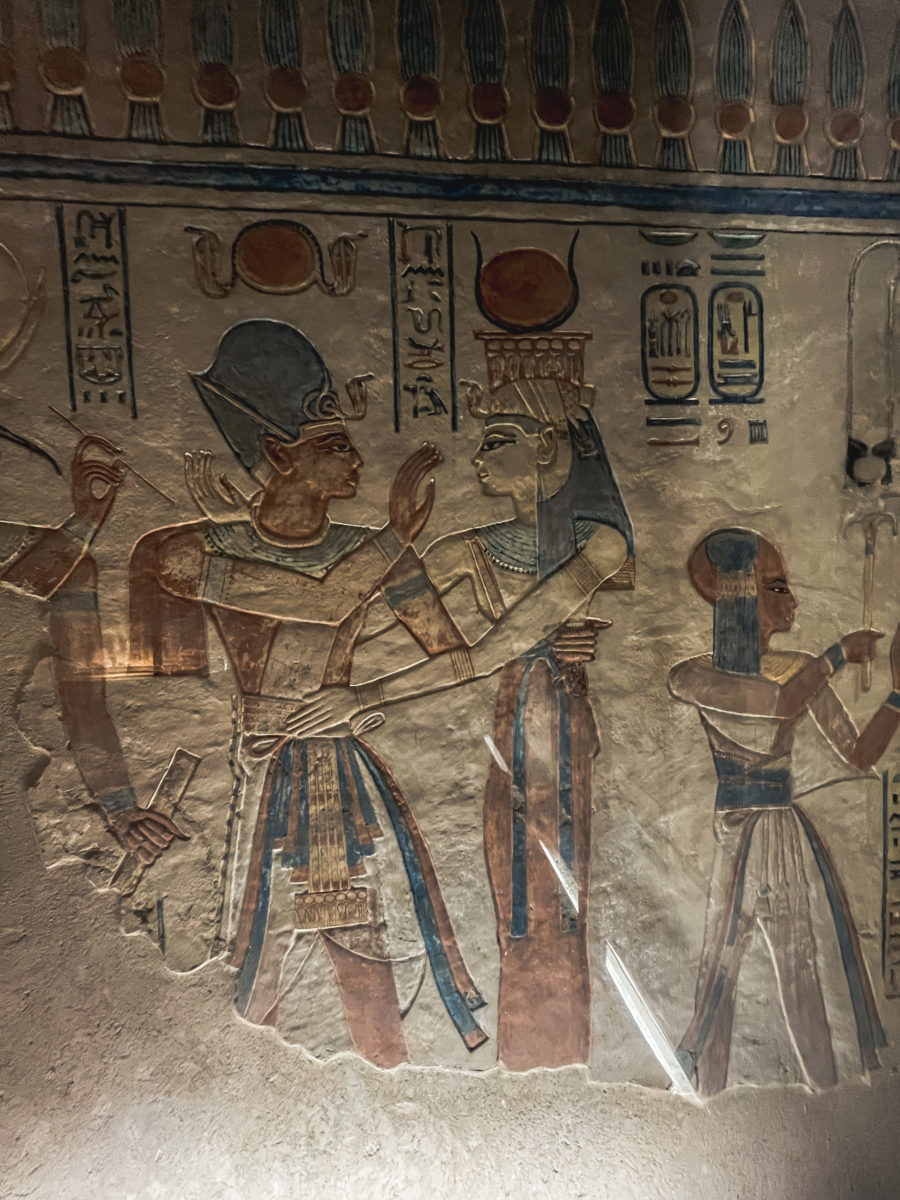

Next, we headed towards another Ramesses, even the first of all, the KV16 tomb, belonging to Ramesses I. It’s one of the smallest in the Valley of the Kings, but it stands out due to the richness of its decorations. Ramesses I, the founder of the 19th Dynasty, reigned for only a year (1292-1290 BC), so his tomb was quickly dug. Its architecture is simple: a sloping corridor leading directly to a single burial chamber, adorned with brightly coloured frescoes depicting the pharaoh facing the gods, notably Osiris, Anubis, and Ptah.

Though modest, KV16 impresses with its detailed hieroglyphs and well-preserved paintings, with particularly vivid shades of red and blue. The red granite sarcophagus of the pharaoh still lies in the tomb, although his mummy was later moved. Today, this tomb offers a fascinating insight into the early 19th Dynasty, marking the transition between the artistic styles of the New Kingdom.

Finally, we made our way to the most impressive tomb we visited, which, even a year later, still fascinates me deeply and awakens the archaeologist within me.

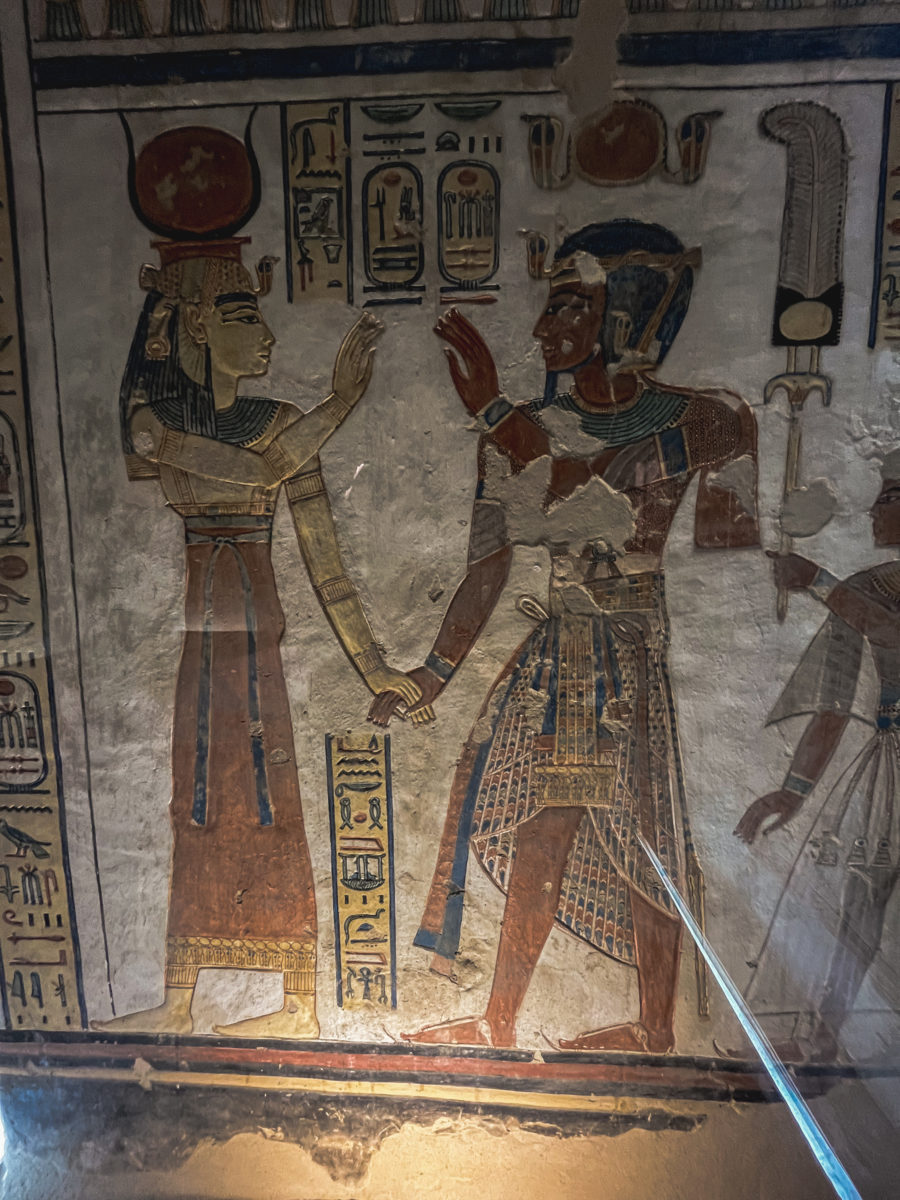

As I write these lines, I fondly recall my first discovery of these hidden treasures, every detail, every colour, and the sense of awe that overwhelmed me during the visit. It was a magical moment, a memory etched in my mind. Here is the presentation of this tomb, KV9, shared by Ramesses V and Ramesses VI.

Originally built for Ramesses V (1149-1145 BC), it was later reused and expanded by his successor Ramesses VI (1145-1137 BC). Its long, sloping corridor, richly decorated, leads to a vast burial chamber where one can admire sacred texts like the Book of Gates and the Book of Caverns, describing the pharaoh’s journey to the afterlife. The ceiling of the burial chamber is particularly remarkable, with a massive representation of the goddess Nut, symbolizing the cycle of the sun and rebirth.

The Temple of Hatshepsut: Discovering the Queen Who Defied Conventions

After exploring the two Valleys, the second-to-last stop of our day took us to a place both sacred and deeply connected to my personal history with Ancient Egypt. As you may have guessed, when I was young, I dreamed of becoming an Egyptologist. And if you have followed my travel stories, you know I am also passionate about historical female figures, especially those who managed to outwit male machinations.

Hatshepsut. Just her name, albeit difficult to pronounce, evokes great strength. Hatshepsut is one of the most fascinating and audacious figures in Ancient Egypt. Daughter of Thutmose I, she became queen and then pharaoh, usurping a role traditionally reserved for men.

She marked her era with wisdom, charisma, and political skill, consolidating her power in a male-dominated world. As pharaoh, she oversaw monumental projects, including the famous temple of Deir el-Bahari, while pursuing a policy of peace and prosperity. Hatshepsut defied the expectations of her time, proving that strength and intelligence have no gender, even though she disguised herself as a man with a fake beard. A pioneer of female emancipation.

The temple of Deir el-Bahari, both majestic and mysterious, seems like a bridge between the past and the present. The temple, like an architectural mirage, stands before us with its imposing silhouette, its stacked terraces, and elegant columns that seem to defy time and harmoniously integrate into the landscape.

The ascent is made via ramps that wind between yellow and white rocks, but the goal is not simply to climb; it is to soak in the grandeur of the place. With each step, we get closer to this masterpiece built by an audacious woman, Hatshepsut, who, despite the norms of her time, succeeded in imposing herself as pharaoh.

As we continue our exploration, we are amazed by the reliefs that adorn the temple walls, telling the story of the sovereign. The scenes show Hatshepsut, not just as a queen, but as a full-fledged pharaoh. In one of the bas-reliefs, she is depicted with the royal beard, a symbol of her authority, walking with dignity and grandeur. These images, far from idealized, reflect the reality of her power. Through these representations, Hatshepsut seems to defy her era, proving that femininity was not a barrier to greatness.

As we venture further, the architectural details continue to surprise us. The columns of the upper courtyard are adorned with floral motifs, symbols of fertility, in striking contrast with the austerity of the surrounding mountain. The hanging gardens, though only evoked in the reliefs, seem to come to life in the imagination, offering us a glimpse of what this magnificent place may have been at its peak.

And then, there is this almost palpable feeling that this temple was built not only to honor the gods but also to immortalize the memory of a woman who left an indelible mark on the history of Egypt. The gentle breeze flowing through the columns seems to murmur Hatshepsut’s secrets, constantly reminding us that she, a woman in a man’s world, left an unforgettable legacy.

At the end of the visit, the temple slowly fades behind us, but its imprint remains etched. Hatshepsut is no longer there, but in this place, she remains, eternal and majestic, ready to defy time once again.

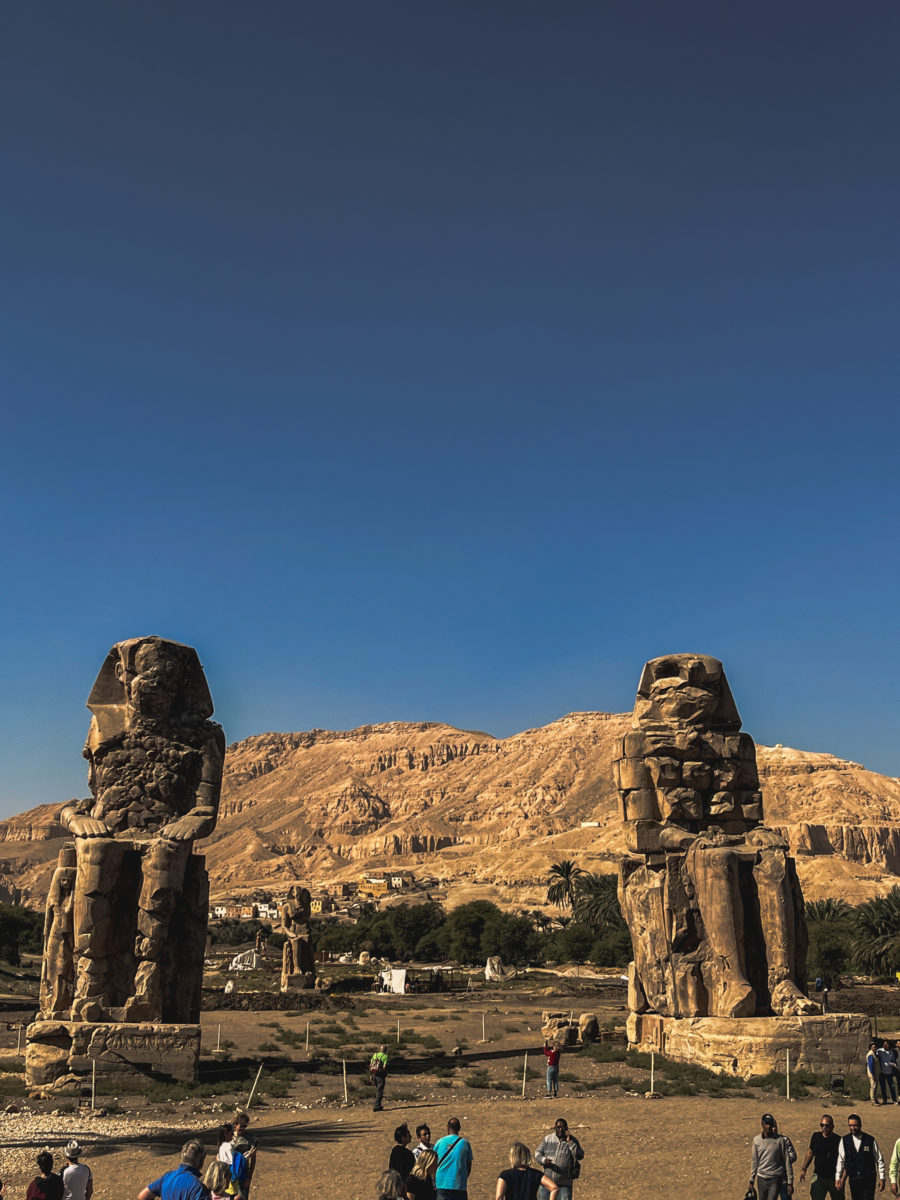

Final stop: the Colossi of Memnon, eternal guardians

Our only free of charge stop of the day, we end our exploration of the west bank by approaching these two large statues that taunt us on every car ride but whose origin remains a mystery.

Although today weathered by time and the elements, these two 18-meter-high giants were once the guardians of the entrance to the mortuary temple of Amenhotep III. Their imposing silhouette is of a power so unwavering, defying the centuries and the desert winds.

These statues, made of robust sandstone, represent Pharaoh Amenhotep III in a solemn and meditative posture, but history has transformed them into symbols of an even greater mystery. For these giants, despite their imposing size, are linked to a particular legend: the strange sounds they produced at dawn, a noise resembling a cry, which, according to tradition, was supposed to be the pharaoh himself speaking to the gods.

This mysterious phenomenon, though now explained by natural phenomena related to temperature changes and humidity, has fueled the imagination of travelers and local inhabitants for centuries.

I remember that when observing these silent statues, it felt as though they were crying out around me the grandeur and majesty of ancient Egypt. Time passes, taking with it the glory of ancient Egypt, but the Colossi remain there, immobile, carrying the echoes of a glorious era, reminding us that some things, even after millennia, escape the erosion of time.